Metabolic syndrome is one of the biggest “silent” health problems affecting many Africans today—especially if you have belly fat, rising blood pressure, borderline or high blood sugar, or you’ve been told you have fatty liver. The reason it’s so dangerous is simple: it’s not just one condition. It’s a cluster of problems that feed each other—and quietly raise your risk of type 2 diabetes and heart disease. (NHS, n.d.; Swarup, 2024)

If you’ve ever said, “My BP is small,” “My sugar is not that high,” “It’s only small belly,” this post is for you—because metabolic syndrome is how “small small” becomes serious.

Table of Contents

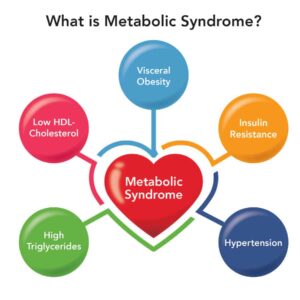

ToggleWhat Is Metabolic Syndrome?

This condition is the name used when a person has a group of risk factors that tend to happen together, such as:

Increased waist size (belly fat / central obesity)

High blood sugar (or insulin resistance)

High triglycerides

Low HDL (“good”) cholesterol

Most medical definitions diagnose metabolic syndrome when you have 3 or more of these risk factors. (Swarup, 2024; Johns Hopkins Medicine, n.d.)

The NHS also describes metabolic dysfunction as a group of health problems that increases your risk of type 2 diabetes and heart and blood vessel diseases, and many people don’t notice symptoms until a routine check shows abnormal results. (NHS, n.d.)

Why Metabolic Syndrome Matters (The “Big Picture”)

Tis condition isn’t just a label—it predicts real health outcomes.

Research has consistently shown that metabolic syndrome is associated with about a 2-fold higher risk of cardiovascular events (like heart attack and stroke) and increased risk of early death. (Mottillo et al., 2010)

And because insulin resistance is often at the center of metabolic syndrome, it strongly increases your risk of developing type 2 diabetes over time. (Shin et al., 2013)

Now let’s bring it home:

Why many Africans are at risk

Across African populations, studies report that metabolic syndrome is common, with prevalence varying by region, urbanization, and diagnostic criteria. A large review focusing on African populations reported notable prevalence levels across regions. (Bowo-Ngandji et al., 2023)

Urban lifestyle changes—more processed foods, sugary drinks, sedentary work, chronic stress, poor sleep—make the “metabolic syndrome pattern” more likely.

How Common Is Metabolic Syndrome?

Metabolic syndrome is now a global public health problem.

Globally, an estimated 20–25% of adults have metabolic syndrome

Rates are increasing rapidly in Africa due to urbanisation and dietary changes

Over 50% of people with type 2 diabetes meet criteria for metabolic syndrome

A large global analysis published in The Lancet confirms rising metabolic risk across low- and middle-income countries, including sub-Saharan Africa (Saklayen, 2018).

The Real Connection: How Hypertension, Diabetes & Fatty Liver Link Up

1) Belly fat (visceral fat) → insulin resistance

Belly fat is not just “extra weight.” The fat stored around organs (visceral fat) is metabolically active and is strongly linked to insulin resistance and inflammation. (Huang, 2009)

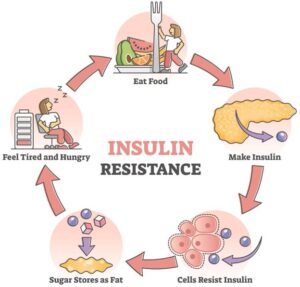

2) Insulin resistance → higher blood sugar + higher triglycerides

When your cells stop responding well to insulin, your body produces more insulin to cope. Over time, blood sugar rises and triglycerides often rise too—this is part of the metabolic syndrome pattern. (Huang, 2009; Shin et al., 2013)

3) Insulin resistance + inflammation → higher blood pressure

Insulin resistance can affect blood vessels and kidney salt handling, contributing to rising blood pressure. (Huang, 2009)

4) Insulin resistance + belly fat → fatty liver

Fatty liver (often called NAFLD—non-alcoholic fatty liver disease) is strongly linked with obesity and insulin resistance. (Fabbrini et al., 2010)

Globally, NAFLD affects around 30% of people and is rising. (Younossi et al., 2023; Le et al., 2023)

So yes—high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes risk, and fatty liver often come from the same root problems.

The Central Role of Insulin Resistance

At the heart of metabolic syndrome is insulin resistance.

Insulin is the hormone that helps move glucose from the bloodstream into cells for energy. When the body becomes resistant to insulin:

Blood sugar levels rise

The pancreas releases more insulin

Fat storage increases, especially around the abdomen

Blood vessels become stiff and inflamed

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention identifies insulin resistance as a major driver of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease (CDC, 2022).

High Blood Pressure and Metabolic Syndrome

High blood pressure rarely develops in isolation.

Insulin resistance causes:

Sodium retention in the kidneys

Increased blood vessel stiffness

Chronic inflammation

These changes raise blood pressure over time. The NHS notes that people with metabolic syndrome are at significantly higher risk of developing hypertension and heart disease (NHS, 2023).

👉 Internal link: Early Signs of High Blood Pressure You Shouldn’t Ignore

Type 2 Diabetes: A Core Component

Type 2 diabetes is often the most visible outcome of metabolic syndrome.

As insulin resistance worsens:

Blood sugar remains persistently high

Pancreatic function declines

Diabetes develops

Research shows that individuals with metabolic syndrome are five times more likely to develop type 2 diabetes compared to those without it (Grundy et al., 2005).

👉 Internal link: Type 2 Diabetes Explained: Causes, Symptoms & Prevention

Fatty Liver Disease: The Silent Partner

Fatty liver disease—now increasingly referred to as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD)—is a key but often overlooked part of metabolic syndrome.

The liver stores excess glucose as fat when insulin levels remain high. Over time, this leads to fat accumulation in liver cells.

A global meta-analysis published in The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology estimated that over 30% of adults worldwide have fatty liver disease, with much higher prevalence among people with diabetes and obesity (Riazi et al., 2022).

👉 Internal link: Early Signs of Fatty Liver Disease You Shouldn’t Ignore

Why Belly Fat Is a Warning Sign

Belly fat, also known as visceral fat, is metabolically active and releases inflammatory substances directly into the bloodstream.

The World Health Organization states that waist circumference is a stronger predictor of metabolic and cardiovascular risk than body mass index (WHO, 2011).

This explains why some people appear “not too big” but still develop diabetes, fatty liver, or high blood pressure.

Why Metabolic Syndrome Is Rising Among Africans

Several factors contribute to the increasing burden of metabolic syndrome in African populations:

Increased intake of ultra-processed foods

High consumption of sugary drinks

Reduced physical activity

Chronic stress

Late diagnosis and poor routine screening

The WHO has warned that non-communicable diseases now account for over 37% of deaths in Africa, with metabolic conditions playing a major role (WHO, 2022).

Can Metabolic Syndrome Be Reversed?

Yes — especially when detected early.

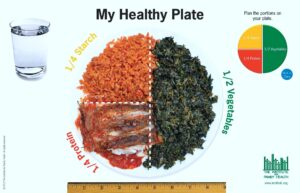

Evidence shows that lifestyle interventions can:

Improve insulin sensitivity

Reduce belly fat

Lower blood pressure

Improve blood sugar control

Reduce liver fat

Losing 5–10% of body weight can significantly improve metabolic markers, according to the NHS and international guidelines.

The Role of Intermittent Fasting and Lifestyle Changes

Time-restricted eating and intermittent fasting may support metabolic health by lowering insulin levels and reducing calorie overload.

A randomised clinical trial published in JAMA Network Open showed improvements in insulin sensitivity and metabolic markers among individuals using time-restricted eating approaches (Wei et al., 2023).

👉 Internal link: Intermittent Fasting Explained: Is It Safe for Africans With Diabetes, Fatty Liver & High Blood Pressure?

Final Thoughts

Metabolic syndrome explains why high blood pressure, diabetes, belly fat, and fatty liver often appear together.

They are not separate problems — they are different expressions of the same underlying metabolic imbalance.

The good news is that metabolic syndrome is largely preventable and manageable with early awareness, informed lifestyle choices, and regular health checks.

✍️ Written by

Vivian Okpala

Public Health Educator | Wellness Coach

Founder, VeeVee Health

References

World Health Organization (2011). Waist Circumference and Waist–Hip Ratio: Report of a WHO Expert Consultation.

World Health Organization (2022). Noncommunicable Diseases Factsheet.

NHS (2023). High blood pressure and metabolic risk.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2022). Insulin Resistance and Metabolic Syndrome.

Grundy, S.M. et al. (2005). Diagnosis and Management of the Metabolic Syndrome. Circulation.

Riazi, K. et al. (2022). Global prevalence of NAFLD. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology.

Wei, X. et al. (2023). Time-restricted eating and metabolic health. JAMA Network Open.

Bowo-Ngandji, A., et al. (2023) ‘Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in African populations’, [Journal article]. Available at: NCBI/PMC PMC (Accessed: 28 December 2025).

Fabbrini, E., Sullivan, S. and Klein, S. (2010) ‘Obesity and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease’, Hepatology. Available at: NCBI/PMC PMC (Accessed: 28 December 2025).

Huang, P.L. (2009) ‘A comprehensive definition for metabolic syndrome’, [Journal article]. Available at: NCBI/PMC PMC (Accessed: 28 December 2025).

International Diabetes Federation (IDF) (2005) The IDF worldwide definition of metabolic syndrome. Available at: IDF PDF International Diabetes Federation (Accessed: 28 December 2025).

Le, M.H., et al. (2023) ‘Global incidence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease’, [Journal article]. Available at: PubMed PubMed (Accessed: 28 December 2025).

Mottillo, S., et al. (2010) ‘The Metabolic Syndrome and Cardiovascular Risk’, Journal of the American College of Cardiology. Available at: ScienceDirect ScienceDirect (Accessed: 28 December 2025).

National Health Service (NHS) (n.d.) Metabolic syndrome. Available at: NHS nhs.uk (Accessed: 28 December 2025).

NICE (2015) Type 2 diabetes in adults: management (NG28). Available at: NICE NICE (Accessed: 28 December 2025).

NICE (2025) Overweight and obesity management (NG246). Available at: NICE NICE (Accessed: 28 December 2025).

Shin, J.A., Lee, J.H., Lim, S.Y., et al. (2013) ‘Metabolic syndrome as a predictor of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease’, [Journal article]. Available at: NCBI/PMC PMC (Accessed: 28 December 2025).

Swarup, S. (2024) ‘Metabolic Syndrome’, StatPearls. Available at: NCBI Bookshelf NCBI (Accessed: 28 December 2025).

Younossi, Z.M., et al. (2023) ‘The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): a systematic review’, Hepatology. Available at: LWW LWW Journals (Accessed: 28 December 2025).

Bowo-Ngandji, A., et al. (2023) ‘Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in African populations’, [Journal article]. Available at: NCBI/PMC PMC (Accessed: 28 December 2025).

Fabbrini, E., Sullivan, S. and Klein, S. (2010) ‘Obesity and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease’, Hepatology. Available at: NCBI/PMC PMC (Accessed: 28 December 2025).

Huang, P.L. (2009) ‘A comprehensive definition for metabolic syndrome’, [Journal article]. Available at: NCBI/PMC PMC (Accessed: 28 December 2025).

International Diabetes Federation (IDF) (2005) The IDF worldwide definition of metabolic syndrome. Available at: IDF PDF International Diabetes Federation (Accessed: 28 December 2025).

Le, M.H., et al. (2023) ‘Global incidence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease’, [Journal article]. Available at: PubMed PubMed (Accessed: 28 December 2025).

Mottillo, S., et al. (2010) ‘The Metabolic Syndrome and Cardiovascular Risk’, Journal of the American College of Cardiology. Available at: ScienceDirect ScienceDirect (Accessed: 28 December 2025).

National Health Service (NHS) (n.d.) Metabolic syndrome. Available at: NHS nhs.uk (Accessed: 28 December 2025).

NICE (2015) Type 2 diabetes in adults: management (NG28). Available at: NICE NICE (Accessed: 28 December 2025).

NICE (2025) Overweight and obesity management (NG246). Available at: NICE NICE (Accessed: 28 December 2025).

Shin, J.A., Lee, J.H., Lim, S.Y., et al. (2013) ‘Metabolic syndrome as a predictor of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease’, [Journal article]. Available at: NCBI/PMC PMC (Accessed: 28 December 2025).

Swarup, S. (2024) ‘Metabolic Syndrome’, StatPearls. Available at: NCBI Bookshelf NCBI (Accessed: 28 December 2025).

Younossi, Z.M., et al. (2023) ‘The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): a systematic review’, Hepatology. Available at: LWW LWW Journals (Accessed: 28 December 2025).

Pingback: Weight-Related Conditions Explained: 9 Serious Health Problems Linked to Excess Weight

Pingback: Hormonal Imbalance in Women Explained: 7 Reasons PCOS, Belly Fat & Fatigue Are Connected

Pingback: Weight Loss Jabs Explained: Benefits, Risks & the Long-Term Impact on Metabolic Health

Pingback: Causes and Risk Factors of High Blood Pressure | VeeVee Health

Pingback: Kidney and Liver Problems in Nigerian Children: Causes, Symptoms & Prevention

Pingback: 7 Early Signs of Kidney Disease You Should Not Ignore (Diabetes & High Blood Pressure Risk)

Pingback: 7 Everyday Habits That Raise Blood Sugar: Dangerous and Unhealthy Triggers Even If You’re Not Diabetic